In the footsteps of Henri Cartier-Bresson, 68 years later

By: Thorsten Overgaard. August 9, 2024.

ARCHEOLOGICAL FACT-FINDING (PART II): When I was in Paris in July 2021, I decided to visit another Henri Cartier-Bresson photo location to try to get inside his head. You may be familiar with my article about "Revisiting Behind St-Lazare 85 years later" from 2017. In this article, it is the 1953-photo, "Escalier côté rue de Crimée".

On this overcast July day in 2021, we walked 25 minutes from our hotel near Place Vendôme to Rue de Crimée and the steps leading to Rue des Annelets, also known as "Escalier côté rue de Crimée."

Revisiting Escalier côté rue de Crimée, 68 years later. Photo: Layla Bego.

Understanding the geometric genius of Henri Cartier-Bresson

The purpoose was to see the scene and try to understand what Henri Cartier-Bresson had seen, and how he might have recognized this was a photo he could take.

Frankly, this is not an obvious location to stop and take a photo, not even when it was more straight-forward lines and overall a cleaner scene back in 1953.

Then again, Henri Cartier-Bresson did have an affinity for stairs, and perhaps the fact that he was faced with this many stairs, made him decide to make something out of it.

The

Rue de Crimée et escalier de la rue des Annelets, 19ème arrondissement, Paris by Henri Cartier-bresson (1953).

What Henri Cartier-Bresson did

This is a 50mm photo, and having been there, the first idea you get when looking at the scene is to put on a wider lens and step back to capture the entire scene. The more, the better.

However, what Henri Cartier-Bresson actually did was to get very close to the stairs and crop very tightly to the most essential elements — leaving out quite a bit of the top of the stairs in the process.

Here I am with the Leica M10-P and a 50mm Summilux-M f/1.4 (set at f/2.0) in the spot where Henri Cartier-Bresson would have made the photo. Photo: Layla Bego.

My photo in 2021 of the Escalier côté rue de Crimée. Leica M10-P with Leica 50mm Summilux-M ASPH f/1.4. © Thorsten Overgaard. This is even cropped to 95% to match the original Henri Cartier-Bresson frame.

It could only have been done this way

Granted, the stairs looked nicer in 1953 than today. I went around the scene and to the other side, to see if I could possibly find another angle that would make sense. I couldn't. This location was the only one where a photograph with such pleasing geometry could be made.

The stairs were constructed around 1920-1924 as part of a housing project in the Butte Bergeyre neighborhood in Paris. As is evident, buildings have changed, as well as lamp posts, cars, and more.

This is me taking a photo again when a dad and his son walks up the stairs. Photo: Layla Bego.

Leica M10-P with Leica 50mm Summilux-M ASPH f/1.4. © Thorsten Overgaard. In this photo, you see more in the frame because I really felt like stepping back rather than forward, so as to 'get it all.' So, there is another insight into Henri Cartier-Bresson: He really was very precise in his composition and wasn't trying to 'get it all' but to make a frame of 'geometric pleasure.'

Henri Cartier-Bresson: Geometric pleasure

Like many other of his photographs, this photograph has some of the well-known elements that often make up a Henri Cartier-Bresson photograph: There is the element of timing (“the decisive moment”), in this case the walking peson with the emptiness around him, and then there are the pleasing geometric shapes that align with each other and create a strong image. “The greatest joy for me is geometry; that means a structure,” as Henri Cartier-Bresson said.

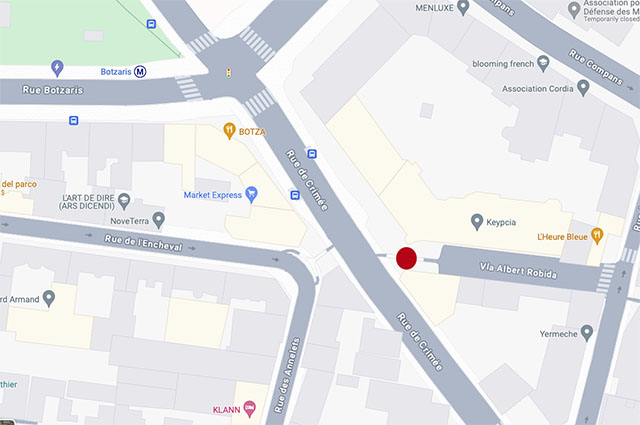

Where is it?

You walk to Vla Albert Robida and then at the end of the little street, you will see the stairs before you.

Henri Cartier-Bresson's affinity for stairs

Most of us have subjects or scenes that trigger our instinct to make photos. One of the things that goes again in the career of Henri Cartier-Bresson, is stairs. Here are some of them:

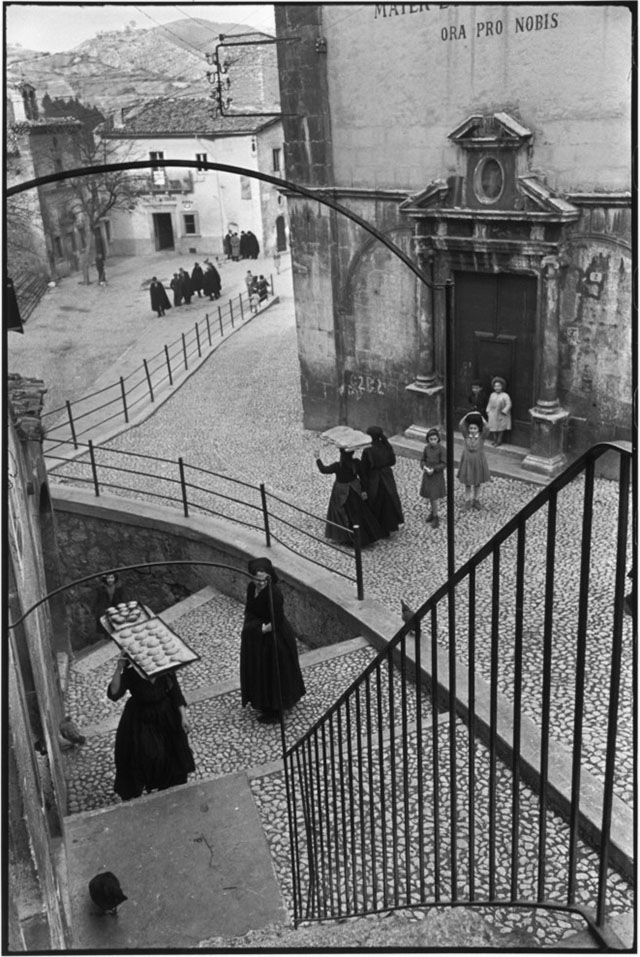

Henri Carftier-Bresson: Scanno, Abruzzo, Italy, 1951

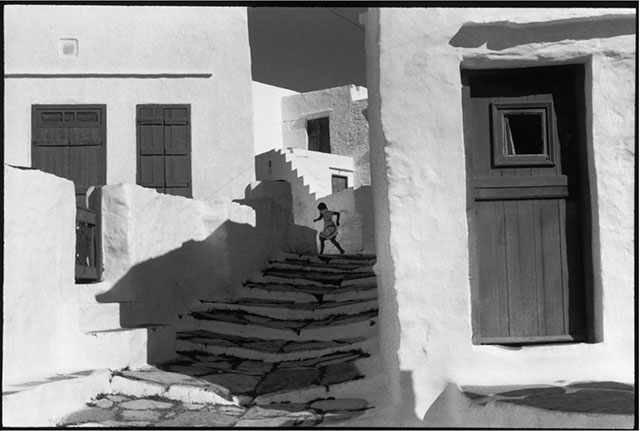

Henri Cartier-Bresson: Island of Siphnos. Cyclades, Greece, 1961

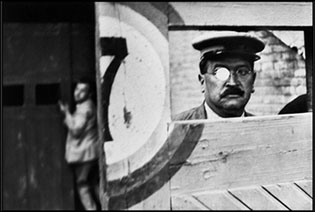

Henri Cartier-Bresson: Hyères, France. 1932

Henri Cartier-Bresson Camondo Steps, Galata, Istanbul, Turkey, 1964

Henri Cartier-Bresson State of Oaxaca, Mexico. 1963.

Henri Cartier-Bresson State of Oaxaca, Mexico. 1963.

Understanding Henri Cartier-Bresson in 6 seconds

I notice that Henri Cartier-Bresson had a period from 1931-1934 where his images were clearly inspired by Cubism, and he did some really inspiring and impressive work. He seemed very enthusiastic.

Then he had a period with quite a lot of Mexican women who were mostly nude (which I guess was also an enthusiastic period, though those photographs are not generally known), followed by a serious political period. After that, he experienced commercial success doing portraits and reportages for magazines, but he seemed less enthusiastic about it himself. Eventually, he went back to painting.

|

|

|

| 1932 - Cubism |

|

1933 - Cubism |

|

|

|

| 1934 - Spanish and Mexican women |

|

1946 - Reportage |

|

|

|

| 1961 - Portraits |

|

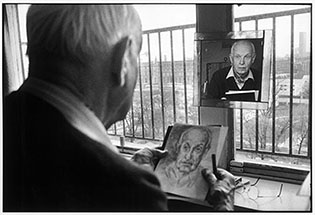

1996 - Painting |

Understanding Henri Cartier-Bresson in six seconds: From being enthusiastic and able to implement advanced Cubism into wordless images, then a few years with Mexican women, to the established years as a gifted portrait photographer, and finally back to his original purpose as a painter.

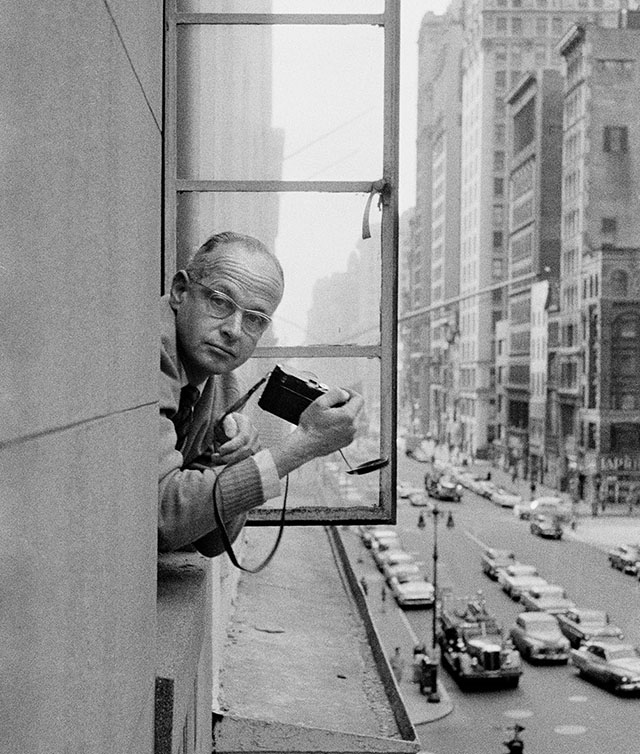

Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) in New York, 1959. © Rene Burri, Magnum Photos.

Which Leica lens did Henri Cartier-Bresson use?

“Henri Cartier-Bresson always used a 50mm,” the saying goes. But it’s also known that he did, in fact, use other lenses. It’s more fair to presume that his preferred lens was the 50mm, just like most Leica photographers use one lens more than 95% of the time. Yes, Henri Cartier-Bresson likely did the same. In an interview years later, Henri Cartier-Bresson shared some details about his choice of lenses:

“The 50mm corresponds to a certain vision and at the same time has enough depth of focus, a thing you don’t have with longer lenses. I worked with a 90mm. It cuts much of the foreground if you take a landscape, but if people are running at you, there is no depth of focus. The 35mm is splendid when needed, but extremely difficult to use if you want precision in composition. There are too many elements, and something is always in the wrong place. It is a beautiful lens at times when needed by what you see. But very often it is used by people who want to shout. Because you have distortion, you have somebody in the foreground, and it gives an effect. But I don’t like effects.”

In 1932, when he made the photograph, Behind St-Lazare, a 35mm lens existed, but only the f/3.5 Elmar, which would not produce the narrow depth of field that the clock tower in the background shows. I did some 35mm photos at f/3.5, and the background is much sharper, even taking into consideration that the original photo from 1932 has mist and/or steam from the trains. The first 35mm Summilux f/1.4 wasn’t made until 1961, so he certainly didn’t use that one.

Maybe as simple as this: He used his first Leica, the Leica-Couplex (Leica D) with the 50mm Elmar f/3.5 to make his most famous photograph, the Behind St-Lazare. He was said to black out the silver parts of the camera.

| |

|

| |

Maybe as simple as this: He used his first Leica, the Leica-Couplex (Leica D) with the 50mm Elmar f/3.5 to make his most famous photo, the Behind St-Lazare. He was said to black out the silver parts of the camera. |

| |

|

So, most likely, he used a 50mm Elmar f/3.5, which was on his first camera he got just two years before. I would suggest the possibility that he might have had a 50mm Hektor f/2.5 (made from 1930) because of the depth of field, as the depth of field almost suggests he might have used a 73mm Hektor f/1.9 (made from 1931), but then he would have had to have been even further back. The 73mm is my idea, simply because it existed at that time, not that Henri Cartier-Bresson was ever known for using that lens. According to himself, he did use 90mm lenses as well, but a 90mm Elmar f/4.0, which was the one available in 1932, would put him very far back (giving a much blurrier fence shadow in the foreground) and, at f/4.0, would not cause the clock tower to be as out of focus as it is.

Join my next Paris Workshop

I always enjoy Paris, and it is a great city to always wear a camera. When we have workshops there, we naturally get to see quite a few interesting details, and some good restaurants and cafes as well.

Read more about the next Paris workshop and my other workshops here: workshops.thorsten-overgaard.com

More to come

Bon voyage with it all. I hope this was helpful for you. Sign up for the newsletter to stay in the know. As always, feel free to email me with suggestions, questions, and ideas. And hope to see you in a workshop one day soon.

/Thorsten Overgaard

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

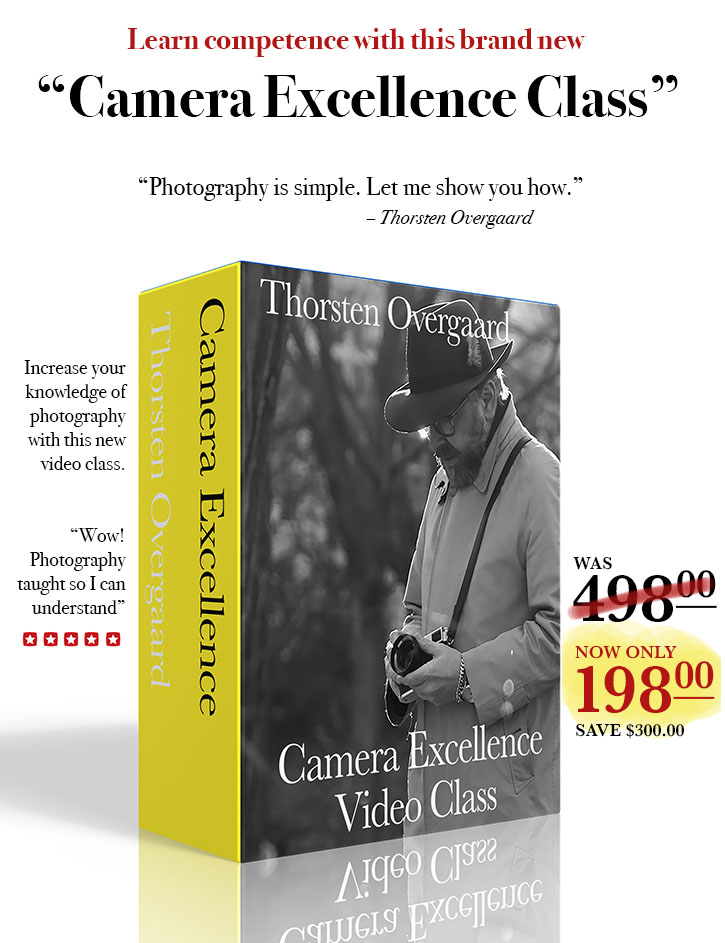

"Photography is simple"

Thorsten Overgaard is one of the best to explain in simple terms how cameras works, and how to get excellent results.

Be competent. Buy and study this easy-to-use video class that explains how to get focus right, what sharpness is, how to get the exposure and the colors right, and more ...

"Easy to apply, photography finally told so everyone can become an expert user"

Normal price $498.00

Explained by Thorsten Overgaard by using Leica Q2, Leica SL2, Leica M11, Leica M10 Monochrom, 35mm film cameras, Leica Digilux 2 and more. |

|

Thorsten Overgaard's

"Camera Excellence Class"

For Computer,

iPad, Apple TV and smartphone.

Normal price $498.00

Only $198.00

Save $300.00

USE CODE: "COXY66" ON CHECKOUT

Brand new. Order now. Instant Delivery.

100% satisfaction or money back.

More info

Item #1847-0323

Released April 2023

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

![]()