By: Thorsten Overgaard. July 30, 2022. Edited August 18, 2022.

Add to Flipboard Magazine.

They say it's a camera, but it's really an idea

When the 99 year old personal camera of Oskar Barnack was sold for 14,400,000 Euros, it was an unbelievable moment. Yet it happened, and I was in the room where it happened. Here is my report from that day, and why it is in truth a celebration of the human ability to bring an idea into reality.

The curious thing is that the atmosphere in a live auction room can become a bit gloating. It's like watching a Rolls Royce getting a parking ticket; it feels good seeing someone with too much money having a bad day. It makes no sense, but it's not our camera and it’s not our money. So it becomes a game.

I’d heard stories at the Leica campus in the days before the auction. Professional camera dealers and collectors, who were stuck with rare cameras or lenses they had paid too much for. “I got bit by the auction fever,” one announces with a shrug of the shoulders while colleagues around the dinner table laughed.

“Let that be a warning to me”, I concluded as the day approached. I had ordered an auction number, but on the day I decided not to pick it up. It’s a piece of paper with a number you hold up when you bid, and without it I wouldn’t be able to get myself into trouble. My dilemma was that there were a couple of interesting things I wanted to bid on. But I decided, I’ll just enjoy the social aspect and not get caught in a bidding war. As the day moves on, I’ll later regret this inability to place a bid as one of the rare and unique items goes for $1,200 and nothing more. On the other hand I also applaud my own decision as another interesting $20,000 black paint item skyrockets beyond $300,000 in a few minutes. Not that I would have followed it higher than $25,000 (I tell myself), but once you fall in love with a rare item in the nicely printed catalog, it’s hard to see it go to somebody else.

One of the product managers at Leica bids on another silver Leica camera and lens, and he gets it for less than $2,000, I think. It comes with a nice original red velvet box with Leica engraved in gold to die for. Such a beauty, I think to myself. I wonder if I had my card, how high a price would we have climbed to, and who would have won. Would the looser ever be able to forgive the winner? And would the winner ever be able to forgive the looser for bidding up the price unnecessarily? It’s a ridiculous thing, even childish. But now that I think about it, I will always envy him that camera, and I secretly consider how I could get back at him. The struggle is real.

The auction room on the day is a sea ofwhite chairs in neat lines, maybe 200 seats in total. Many of the chairs are empty because it is that kind of event where people prefer to stand by the side walls or in the back of the room and not make the commitment to sit in a chair in a room where the biddings will soon fly through the air.

The real power of the room is the approximately ten auctioneer staff sitting by a long table to the right and in communication with hundreds of invisible bidders via telephones and computer screens.

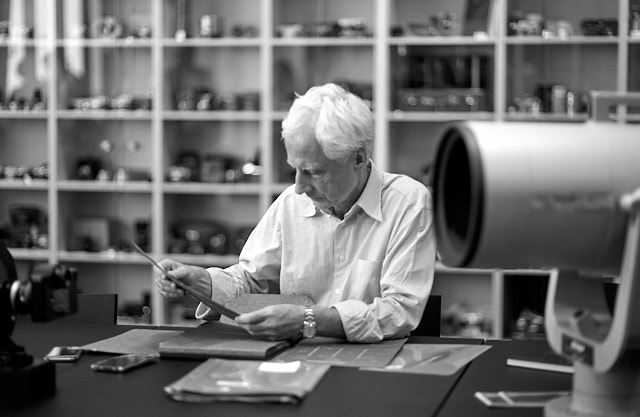

Auctioneer staff getting ready to communication with hundreds of invisible bidders via telephones and computer screens. © Thorsten Overgaard.

With a 5 – 6 hour long auction ahead of us, the No 105 camera that Oskar Barnack made for himself and personally used 99 years ago, conveniently comes up as the 5th item of the event.

As it appears on the big screen (the real camera is in a room next door), there is a short moment where the air leaves the room, then fills with expectation and readiness. The auction leader, who’s a well-known face in Germany from a television program about evaluating antiques, announces in the microphone that the bidding for this particular item starts at 1 million Euros.

The atmosphere is a bit like a day at the horserace, just before the race begins. The bidding takes off in the same manner: A handful of bids erupt quickly, like horses leaving the gate. But then, there are a few unpleasantly long pauses and even though it’s only a few seconds in real time, that day it was a slow drag reaching the 2 million mark. The catalog had listed it worth 3 million (and possibly more). I had personally guessed it would reach 5-6 million. I’m not sure anymore.

At 2 million there is another slightly disappointing pause. Long enough that we start to adjust ourselves to the idea that maybe that was all the fun and try to adjust our mood not to be disappointed about it. 2 million is also a decent amount of money.

The auction leader scans the room for interest or movement, balancing his mood between being ready to end with no tears and leaving space for someone to change their mind.

We wait. People start looking to the sides and behind them, hoping someone will add suspense to the auction by nodding a bid.

© Thorsten Overgaard.

Just when it feels like it’s time to end the bidding, the bidding takes on a life of its own, and it goes upwards to 3, 5, 7, 8, 9 million, and – with a short hesitation – 10 million. At this point, the auctioneer, who’s self-confidence has instantly sky-rocketed, announces that now he only accepts bidding in increments of 1 million or more. Something for all to think about.

Also somewhat relaxing, we’ve reached a point where there’s no shame in being a spectator. There’s no shame in not bidding in brackets of 1 million. We can lean back and enjoy the show.

It changed quickly from a boring auction into something else. It is a rock concert at this point. Many people, including Leica owner Dr. Kaufmann (sitting just in front of me), have taken mobile phones up in front of them to record the moment, like it was a Justin Bieber concert.

The bidding continues in leaps of 1 million with few second intervals and ends at 13,000,000 Euros plus auction fees. A total of 14,400,000 Euros will be transferred from someone’s account in the next few days, and the camera will be delivered. Now the room is already onto item 6 – an item which I don’t remember, in the same way as one doesn’t recall what was said to one during the week just after one’s first kiss.

It's still possible that they buyer realizes he or she can’t pay, and then I think the item goes to the next-highest bidder. But not the case here, the deal was finished and the camera delivered to the unknown buyer.

It was as a Justin Bieber concert. © Thorsten Overgaard.

The aftermath: "I'm sorry you feel that way"

In the age of feeling offended by anything, it should be no surprise that the discussion arose in the days afterwards about whether it wasn’t the duty of Leica Camera to acquire and preserve this unique camera, or whether it didn’t belong in a museum.

The story is that Leica Camera already has several of the original prototypes from different stages, so they hardly needed to acquire and secure each of the 25 prototypes as well.

Also, this very camera originally was in a museum until 1963 when the owner, the son of Oskar Barnack, sold it to an American collector. So, factually there is nothing wrong with the camera being sold to someone who cared enough to pay 14,400,000 Euros for it.

Oskar Barnack's personal Leica no 105. © Thorsten Overgarad.

Then there is also the feeling of being offended that someone can spend US $15,100,000 on a piece of metal. I think that to some, $15 million equates the same as $5,000 for others. So, I’m sorry if you feel that way.

The fact is that few even knew this camera existed until it appeared in an auction catalog from Leitz Photographica Auction Vienna, so how can you miss it now that it’s back into oblivion? It took a wealthy collector to make the rest of us realize the value of this camera.

And it’s not over yet. Maybe the collector is going to put it in his own museum, or maybe let MOMA put it on display.

My own afterthought is this, and the reason for this article: What was it that was bought for 14,400,000 Euros?

A collector who knows what he is doing. Inspecting the blueporints of the Leica, which are for sale. "I like papers" as hen mentions. The blueprints, in the end, was sold close to estimated price, as if nobody noticed that these contains the sketches behind the 14,400,000 Euro camera. © Thorsten Overgaard.

They say it's a camera

While the auction offered a moment of entertainment in seeing Oskar Barnack's camera become the most expensive camera ever sold, the real acknowledgment belongs somewhere else.

It might appear that the camera is a engineering wonder, and in a way it is. But in itself it is just pieces of metal shaped by hand and put together to perform mechanical functions. What the real wonder and value of this camera holds, is the power of the human mind to dream ideas and form matter such as to perform those ideas.

Technology, when it is important, is vertical; that is when things take a jump to new heights and change the way the world works. Like the railroad, the steam engine, electricity, the internet. Vertical technologies are those that change the world.

Most other things we look at are horizontal expansions of those by now already existing technologies which were once just vapor thin ideas. From that moment something comes off the genius’ drawing table and becomes reality, the development becomes horizontal. It becomes business, which means it is simply more of the same, wider distribution to more people, lower prices, bigger bottles, three for the price of two, a new improved model every 18 months, interest-free financing or a subscription. But the basic idea stays the same.

The Leica that Oskar Barnack envisioned and made prototypes of 100 years ago, was a vertical technology in that it didn’t exist before, and once he brought it into reality, it changed everything and everybody now takes that technology for granted.

Kodak did make a $1 box camera before the Leica, but the Kodak didn’t inspire all future development in the camera industry. Nobody made copies of the Kodak box. The Leica birthed a photographic industry that still benefits from this idea, and in the first many years all camera producers in Japan, Russia and Germany outright copied the Leica.

The concept of the original Leica camera

The concept of the Leica could be stated in short: Compact, portable, durable, focusing at a distance, controlling the exposure, controlling the light by the help of high-end optics, automated film loading by using rolls of 36 picture frames. Advanced, and yet so simple that every person could use it.

Simplicity was part of the concept. The first ads for the Leica showed everyday people in everyday situations as the users of the Leica camera.

Precision assembling was also part of the design concept from day one, so much that it inspired Jonathan Paul Ive and Steve Jobs in the design of the first iPhone many years later.

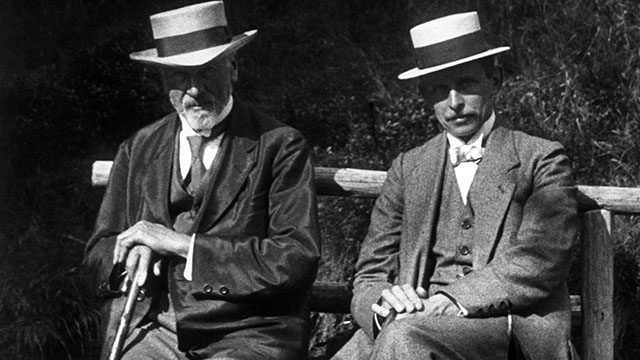

Ernst Leitz and Oskar Barnack.

If Kodak’s $1 camera had been the mover and shaker, today’s cameras would be paper boxes with plastic optics and no control of focus or exposure time. It would have been a different world. That is the influence of Oskar Barnack.

This personal idea of Oskar Barnack’s that he brought into reality has resulted in many millions of cameras and lenses being sold. Each of them fundamentally the same idea, but with different model names and refinements and features added. Leica No 105 is not far from Leica M3, and Leica M11 is fundamentally the same idea, with added electronic features to solve mechanical functions.

Oskar Barnack invented this little piece of vertical technology that the camera No 105 symbolizes. Together with Ernst Leitz (who owned the factory) and Max Berek (who designed the first lenses), they were bound together in a sense of mission to make this idea of a small portable camera a reality, a camera that even housewives and children could operate.

The skill of Oskar Barnack was that he could get an idea, he could hold onto that idea, he could understand more about that idea, he could envision the idea to become reality, and he could endeavor in the workshop creating that idea into mechanical technology that matched his vision, give it life and future. He could consistently believe in the idea for years through modified experiments and prototypes so that it materialized into what we today recognize as the Leica.

The celebration of the human mind

The skill of Oskar Barnack was that he could get an idea, he could hold onto that idea, he could understand more about that idea, he could envision the idea to become reality, and he could endeavor in the workshop creating that idea into mechanical technology that matched his vision, give it life and future. He could consistently believe in the idea for years through modified experiments and prototypes so that it materialized into what we today recognize as the Leica.

The point I’m making is this: The Leica isn’t made of metal, it’s made of ideas.

| |

|

| |

Oskar Barnack self portrait ca. 1914 |

| |

|

That a camera could be made portable was the vision of Oskar Barnack. Until the Leica was invented by him, the camera obscura were large boxes that were best used in a studio or set up on a tripod outdoors.

The story about how he got there is two-fold, but in both ways expresses a want to solve problems and improve the way things worked.

One side of the story was that Oskar Barnack due to asthma, couldn’t drag the large cameras up the mountains, so he wanted a camera to be smaller.

The other side of the story was that Oskar Barnack was really into moving pictures (movies) more than he was into still pictures. He was dumbstruck fascinated by the possibilities of the moviemaking, which resulted in a metal housing for a motion picture camera (so far they had all been made of wood). So, the more likely story as for why the Leica was invented was that it allowed him to test film stock. A bit like the M10-P ASC camera today can be used as a director’s viewer to prevision frames and lens effects, a small metal box with a snippet of film could be used to take stills and develop the film; and thus work as a test of that film stock.

A lentil, a tent and a pencil - The words of photography

The story of the Leica camera, as well as the relatively young subject of photography, is a great example of a new subject so non-existent at the time of invention that words to describe it really didn’t exist and had to be made-up as they worked it out.

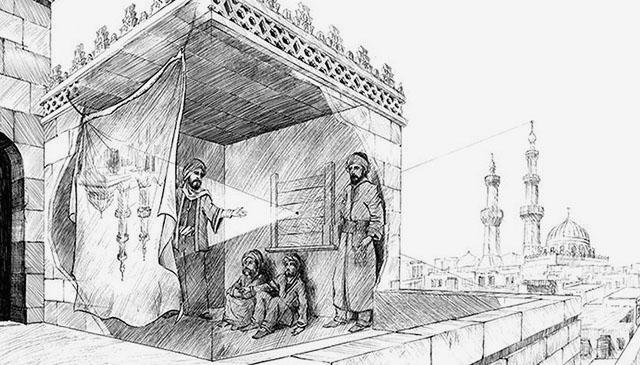

Camera

The word “camera” is slang for “camera obscura”, which means a dark room. The term comes from Spanish soldier tents. Originally, it was discovered that if you poke a small hole in a wall into a dark room or tent, light peaks through, and if the hole has a certain small size, it acted as a device to assist light. This was the first actually discovery that you can form an image by light, and that it’s apparently a built-in feature of how the universe works. This is something almost every child discovers at some point when they sleep at their grandmother’s house and light comes through the keyhole: There is an image formed on the wall from that.

Since it was officially discovered some 2,500 years, nothing much was done with it. It took more than thousand years before artists found it as a sneaky way to project an image of the outside world onto a wall and so made it possible to make a precise sketch with the correct proportions and perspective.

A Camera Obscura in that Camera means chambre (room) and Obscura = dark.

Photography

Not until 150 years ago someone eventually got the idea to record the light with the use of chemicals and metal plates. Photography was born, and the word photography means “writing with light” and we use the short slang “photo” mostly.

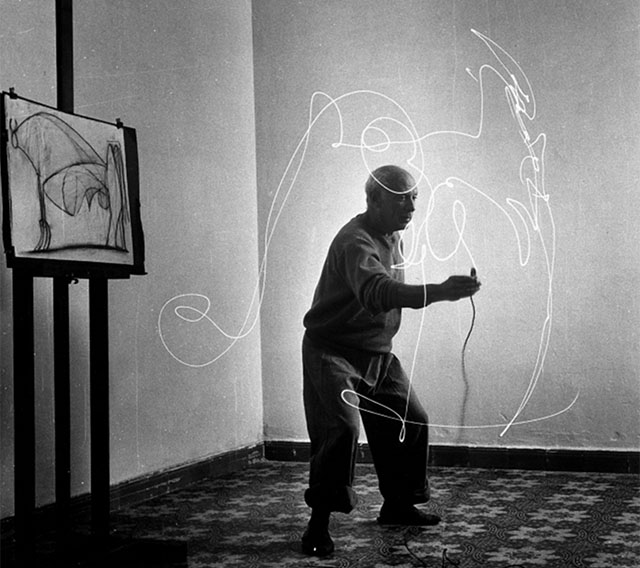

Picasso painting with light in a photogtraph from 1949.

Optics and lenses

Along the way, optics was discovered and developed, and by optics we are talking about shaped glass called lenses. The word “lens” refers to a lentil-shaped form, so here again we have a new technology that was so foreign that the name for it became what it looked like in shape.

Not unlike many other things in life. The word “bear” comes from German “big brown one”. They called it what they saw. Soldiers’ tents, lentils, writing with light.

The word lens derives from lentil, because of the similar shape.

If we consider that the urge to express oneself visually was born 65,000 years ago in cave drawings, then it puts things into perspective that it took all that time until now to see image-making an everyday thing, (now omnipresent with any smartphone camera).

The idea of communicating visually, and the idea of preserving what we see, seem to be inherent in the human soul. After all, we are all born with an ability to see, record and recall images with our mind. But the tool to make this everybody’s ability is what Oskar Barnack and his camera no 105 signify.

In reality priceless, but now evaluated at 14,400,000 Euros.

As always, feel free to email me with questions, comments and ideas.

- Thorsten Overgaard

This article was inspired by two books that you can buy on Amazon:

"Zero to One" on vertical technology and making ideas into global business, and "Dianetics 55" about the ability of the human spirit to form ideas into reality.

Epilogue on the Leica 0-series no. 105

Accordig to Erwin Puts Leica Chronicle book of 2014, the 0-series cameras, amongst the first 25-31 or so cameras made to test the cames and the market, Barnack's own camera was the no. 112 while the no 105 was given to the Leitz director, Dr. Henri Dumar. Here is the list fo cameras:

Here is the list of Leica Null-Series cameras

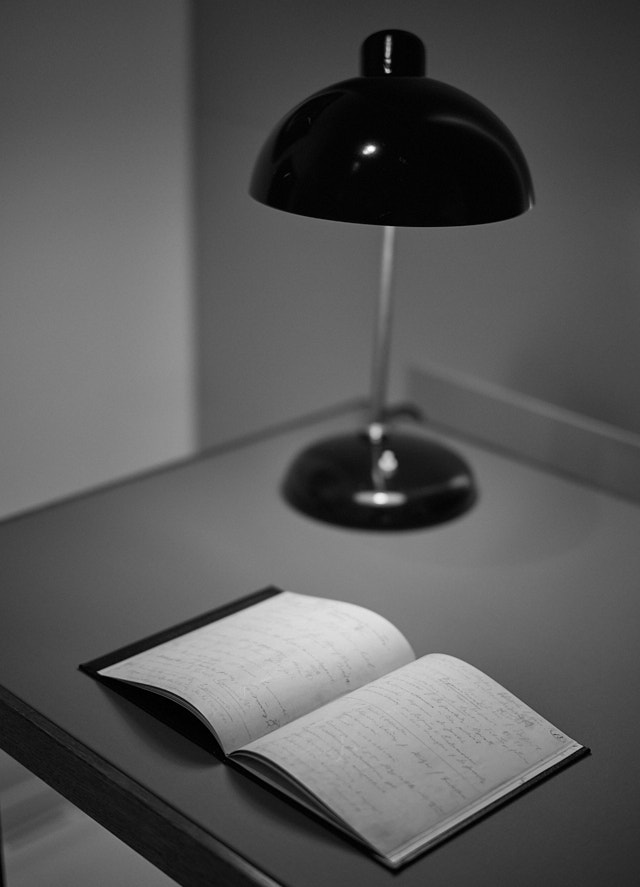

Based on handwritten entries in the internal journals.

101: (A) Bauer, Leitz manager

102: Ernst Leitz junior

103: Kipper Berghäuser, Fricke/Rochester 104: Leica Museum

105: Dr. Henri Dumar, Leitz director

106: Max Bereck ?

107: Leitz Patent, New York

108 & 128: Zack, Leitz manager

109: Leitz/Kutschinsky, Berlin, dealer

110: Kittner ?, Wien ?

111: Zeiler, New York, dealer

112: Oskar Barnack

113: Bergmann, Dr., Berlin, representative for Leitz

114: Klutze, Gießen, scientist

115: Kraft, William, Wiesbaden, dealer

116: no entry

117: test camera

118: Eicken, Prof. Berlin, scientist

119: Kipper Begasseur/Oberhausen

120: Bermann Berlin, dealer

121: no entry

122: Sauppe New York, dealer

123: no entry

124: no entry

125: no entry

126: Micael Becker, photographer

127: entry stroked through

129: Winterhoff Gießen, dealer

130: not readable

131: not readable

132: not readable

133: not readable.

![]()