By: Thorsten Overgaard. August 10, 2010. Updated August 2, 2018.

I got an e-mail asking for advice on shooting rock concerts and other stage performances, so I thought I might as well make it into an article. And here it is.

How to get there (accreditation)

Usually to shoot concerts, you need an accreditation. Often it is the venue that grants accreditation, but sometimes it requires permission directly from the artist, often represented by the record label or the tour manager (the artist's manager who travels with the band). Apart from the needed communication line (the right phone number or the right email), it's usually easy.

One problem can be that there are too many photographers already, another that the artist allows only "local media" (and not potentially international media or distribution), a third that the artist simply doesn't like being photographed (for that job, in that period, or just generally).

Abdullah Ibrahim is said to be one who doesn't like it, though I was allowed to photograph him once. Prince was another known for not allowing it. Muse are known for not allowing it as they have their own photographer, and so on.

Ibrahim Abdullah performing at the Aarhus Jazz Festival. © Thorsten Overgaard.

The worst scenario is stadium concerts where it's often the local organizer who gives accreditations. As it is usually an organizer who only has a commercial interest in that one or few concerts he is organizing, they have no real interest in promotion after the ticket sales have closed (and your photos would be of interest only for future organizers who need a photo to promote their concert). But try in any case; often it's the tour manager or artist who decides as they have an interest in creating PR for future concerts.

Technical

The lights on stages are mostly tungsten, no matter what color filters are being used. Sometimes you are lucky and there is a pretty stable "white" tungsten light pointing down at the artists most of the time so you can get realistic colors as a base. Sometimes the light is ever changing in colors, and hence the skin colors will change dramatically. But the light you set for is still 3200 Kelvin (Tungsten light). Because that is the closest you get.

You might find out afterwards that there were older theater lights used and this explains why tones are a bit warmer than might be expected from tungsten lights. And on more and more stages you will notice the tungsten lamps in the ceiling, only to realize when you are back home editing that they were in fact LED lights in disguise as tungsten lamps. It happens more and more as the LED lights are smaller and more economical to run and give less heat. However, LED light varies a lot in Kelvin temperature, their quality of light, and will have a weird way of changing when you adjust the color temperature in Lightroom or Aperture. It's simply not light, as we know it.

Mike Sheridan and Mads Langer giving concert in LED light in The Royal Theater in Copenhagen, Denmark. If you turn the dials a bit in Lightroom, the colors and all changes completely. A good idea is to get the exposure correct in such cases so you don't have to adjust anything. © Thorsten Overgaard.

My handling is always to set the camera for 3200 Kelvin, unless there are special lamps involved such as 12,000-Kelvin spots or real special equipment (and I have a chance to measure it so I can get my settings right).

For fashion shows I try to get a reading on a WhiBal "grey card" before the show starts so as to have a very precise reading (because the clothing is the most important subject in a fashion show, and thus the colors are essential). But 90% of fashion shows are in the area of 3200 Kelvin, so if I can't get a reading, 3200 Kelvin is the setting to use (unless it's daylight lamps which are very expensive to use but give the absolute best light for photos and audiences).

C. V. Jørgensen, photographed with Leica R9/DMR and 35-70mm Vario-Elmarit-R ASPH f/2.8 at 400 ISO. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Exposure control

The way to shoot a stage is manual. You shoot a few in the beginning, eventually on some sort of auto or semi-auto, then you look at the results and adjust it to a manual position where it looks right. Pay attention to how the light changes on the subject during the concert - usually there is one setting 90% of the time, or three types of light on that person, or the light changes from tune to tune.

But any change that happens, you adjust manually for it, and then remember what you have to change back to when the light that was before, reappears. Sometimes it's changing rapidly, and then you have to guess in a hurry.

Jesse Stevenson. Leica M9 with Leica 50mm Noctilux. You have to have a manual setting based on how much light is usually on the face of the artist, then go with that. With the camera on auto, Jessse Stevenson would be a silhouette in this photo. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Shooting auto will most likely ruin your shots. There is too much contrast on stage for auto to figure out the correct exposure on the artist, and too many bright lights in the back that go on and off. So rely on your vision and instinct, and don't panic. You will get perhaps 70% of our shots that are not usable because of exposure, out of focus, the artist disappeared from your frame the instant you pressed the shutter release. And so on.

But as long as you get the shots you need, don't worry about all the ones that didn't work. Concert photos are the type of files where you will have the largest percentage of shots that do not work - because you can't control the everchanging light and movement on stage.

The lens and camera

For most stages you can use everything from 28 to 90mm, for larger stages you may want something larger. It also depends on the amount of light. A sharp lightstrong lens is of more value than a tele lens that requires a lot of light; because you can crop the lightstrong sharp lens, whereas you can't hold the big tele lens steadily.

The usual location for concert photos is just in front of the stage (in the pit below), so you're pretty close. So if you want an overview photo or the artist(s) in full figure, you often need to go 28mm or 35mm.

Flash is not allowed for stage photos, nor for fashion shows. Though you will see someone use flash from time to time, either because they don't know how to turn it off, or because they simply don't know.

A silent camera is perfect for any stage work, especially jazz, classical, electronica and other types of concerts where a slapping mirror is heard easily. I also often turn off the display and any blinking red lamps on the camrea, just to be sure I'm not the center of attention for the audience behind me.

Manual focus is what I mostly use but I have also used autofocus cameras for stage work. Smoke on stages will always confuse autofocus cameras and is in general bad news for any type of visual recording. Though you can preset and lock autofocus on a given spot and wait for the artist to hit that spot, and then it will work out all right.

Tim Christensen of Dizzy Mizz Lizzy. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Timing is of essence for stage photography. Some shoot like machineguns and never really hit anything of interest anyways. You’ve got to get into the rhythm of the show, foresee when an outburst or some expression will happen or re-appear and prepare for that. If something of interest happens, you may want to shoot a long series to make sure you got it. But otherwise, look and listen and have an idea of what you want to get.

Look for particularly interesting compositions of people, reappearing light settings that look dramatic or otherwise, and of course the money shot: Straight eye contact between the artist and you.

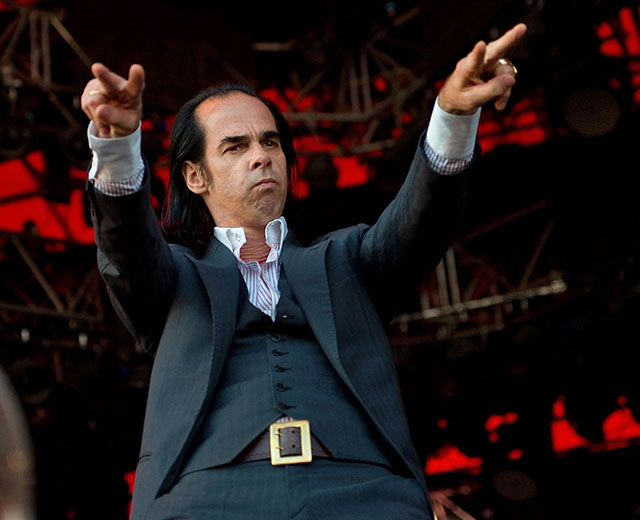

Nick Cave doesn't stand still much. Some you nail the focus, some you don't. © Thorsten Overgaard.

If it is theater photography, one or a small series of images must tell the story (and create interest amongst others to go see that theater play based on the images). It requires timing! If it is rock 'n' roll, the images must sing and have rock 'n' roll blood, sweat and tears about them. That is why it is you and not just anybody who's standing there. This is entirely your contribution. It doesn't happen by itself. I've seen even the liveliest concerts made into still life by machinegun photographers who thought the camera made the photos.

Manners in front of the stage

Photographers are usually allowed to photograph during the first three acts. Sometimes it's limited to two or some other type of limitation. If you are with the artist and get an AAA (All Area Access) you can stay during the entire concert, work backstage and often also on stage (provided you can work discrete and doesn't fall over cables and such) - and all security people will know what an AAA means and let you do your job. Just keep it visible on your chest.

Backstage in the makeup. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Mostly the artist won't notice who's amongst the photographers, so hand signaling, yelling and such is absolutely not the way to go. Stay in the spot in front of the stage and behave with respect to the artist who has the most important job. You can move around, put a camera on the edge of stage and so on, as long as it doesn't disturb the artist or the paying audience behind you.

Roskilde Festival. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Sometimes it would have been a good idea to bring a ladder or something, but mostly you don't see it. And somehow it works out anyways.

Before the concert photographers line up, and even when there is no cue, everybody knows their place in the virtual cue, and the first ones choose their spot first. And usually you stay pretty frozen at your spot until it begins. Even when you are worried you won't be able to see through the other photographers to the stage, it will work out.

It is incredible how little space is required for a lens to see through and how close photographers can work side by side. And you may also be able to move around during the three acts. Just make sure you don't go in front of other cameras, don't hold up a camera so it shadows over the others’ views, keep your elbows along the side and so on. All in all, don't do to others what you wouldn't want them to do to you. Being in front of somebody else means you take up as little space as possible so they have a chance to get a view as well.

Dave Growl. Leica M9 with 90mm Summarit-M f/2.5. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Remote controlled cameras put onto the stage for example in front are seen more and more if you want to move around with a tele but also want that center front-row look from a position where your body can't sit.

A thing to remember is that the best photos are not necessarily to be gotten from the spot where all the other photographers are (which is usually as close to the artist as possible), and sometimes you don't need 15 or 20 minutes to get your shots. So just because everybody else seems to shoot like machine-guns for 20 minutes, it doesn't mean it's the right strategy.

Get an idea of what you want in terms of "critical close up" photos of the artist(s) and secure that space in front of the stage for that. Then, start thinking about other interesting images and move around. Then you will get something different that no one else has gotten.

Portraits

Sometimes, if I have special interest in an artist, I will ask for one-on-one time. It's not that often it can fit into a schedule, and if I don't have a great idea and/or a specific use, I won't bother the artist to do it. After all, most artists travel, do rehearsals, perform and travel. And if they have energy left, they will have personal friends, colleagues and family in the towns they visit, whom they will spend a little time with.

But it is perfectly ok to ask for time to do a portrait if you have a mission and a good idea with it. If you can do a great portrait, go for it. If you just want to use the camera as an excuse to get closer, don't do it.

Percussionist Hossam Ramzy of Led Zeppelin photographed with Leica M9 and Leica 50mm Summicron-M f/2.0 at 400 ISO, manual white balance. Lit by two ARRI lights and one silver reflector. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Artists should be allowed to use the images

Usually when I shoot artists, I allow them to "use the images for own prints and websites but not third party usage such as PR photos." It's fair to exchange for their time and name, and especially if it is an upcoming artist, I like to support his or her efforts by providing some great photos for his or her own website, Facebook, Myspace, etc.

When it becomes commercial, which is when a record label wants to use my image for a cover, a band wants to make money on selling a picture book at the venues, a publisher wants to publish and sell a book with my image in it, or a magazine or newspaper wants to print the image in the publication they sell - then it costs money.

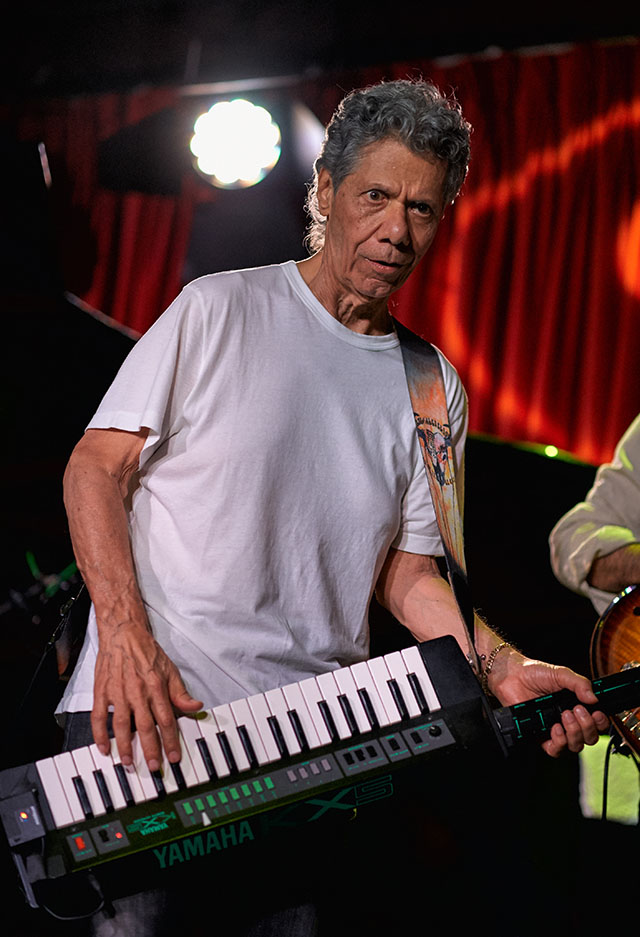

Chick Corea. Leica M10 with Leica 75mm Noctilux-M ASPH f/1.25. © Thorsten von Overgaard.

Beware that artistic businesses such as the record industry, magazine and publishing industry, fashion industry and traditional art as the type displayed in museums are filled with people who will suggest providers of content to those CD publications, museum exhibitions, newspapers, etc. to "be happy that we like your work" or "we'll credit you but we don't have any budget," etc. Whenever you meet such a person, be aware that this is a person who can't make music, images, paint a painting or do fashion design himself, but he loves to invalidate your ability to do so, to a point where you will succumb and give away your work. Because then he can make a living. The answer to those people is simply: Fuck you!

The reason record labels exist, art museums exist, newspapers exist, fancy magazines exist, concert halls exist, is because there is talent who can fill content into them. It's not the organizer who fills the stadium where George Michael performs; it's George Michael's talent. Speaking of which, he has had his fight with record labels. And so had Prince, who, for a long period couldn't use his own name Prince, but instead had to make up a symbol until he got back his right to use his own name. Rolling Stones had to go through similar cases back in the 60’s where someone claimed to own everything they ever made, and everything they would ever make!

Prince performing at the Roskilde Festival 2010 in front of an audience of 74,000 people. He got paid in the range of $4,500,000 for performing - and that is how much a talented artist is worth for a performance which lasted about 135 minutes. © Thorsten Overgaard.

Sorry to bring this up, but if you want to work as an artist, with artists, amongst media and record labels, you have to know who you are and what you stand for. Without artists there is no music, no concerts, no joy of creation. And without great imagery there won't be any fancy magazines or nice looking reviews on websites.

So do great imagery, but be aware that it is actually yours, and that it is worth money and goodwill. So don't succumb when someone says otherwise.

And whenever someone use your images without permission, bill them twice the usual amount. The law will back you up. And blog about them, like I have done , and like Steve McCurry has done.

Thorsten Overgaard

Also read

"Pictures have value"

"What is Copyright"

#1201-0811

PS

You can see the slideshow from Roskilde Festival 2010 right here

International singer-songwriter Ole Boskov at Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen. © Thorsten Overgaard.

![]()