By: Thorsten Overgaard. June 25, 2017. Udpated August 10, 2024

Add to Flipboard Magazine.

In the footsteps of Henri Cartier-Bresson 85 years later

ARCHEOLOGICAL FACT-FINDING: When I was in Paris in May 2017, I rented an apartment a couple of minutes from the Saint-Lazare train station, where Henri Cartier-Bresson made one of his most iconic photographs, and then I spent some days exploring the scene as an archeological pastime.

The closest I got to a re-creation of the famous Henri Cartier-bresson photograph. Leica M10 with Leica 50mm Noctilux-M ASPH f/0.95 at f/2.0. © 2017 Thorsten Overgaard.

The project started a long time before May 2017: My fascination with this photograph began when I was a teenager and knew nothing about Henri Cartier-Bresson. I must have picked up a book from the library because I was exposed to a few of his photographs, as I now realize. One of them I even used as inspiration for a magazine cover I was drawing (I was doing comics when I was a teenager). Knowing nothing about anything back then, I can truthfully say that it was the photograph, and not the person or the history behind it, that impressed me.

I knew it when I saw it the first time—this is a great photograph. It wasn’t until later in life that the name Henri Cartier-Bresson, the Leica, and the history of photography took on significance as I learned he was recognized as the most influential reportage photographer of the century.

In a way, I feel I discovered Henri Cartier-Bresson before anybody else. It wasn’t actually that way, but in my world, I did, in fact, discover him before I knew who he was.

As a side note, that’s how I have always studied photographs. I always looked at the pictures, and only in the cases where I found the photographs fascinating did I start getting interested in the name behind them. That’s the reason when someone asks who my favorite photographers are, I never have any names. But I do have photographs, I’m sure.

Where is it?

Today, I have an original print of "Behind St-Lazare" from the American Express Exhibition in New York in 1983. I have had the mixed pleasure of having people look at the framed photograph and ask me all sorts of questions. While Henri Cartier-Bresson is, to me, a household name that "everybody knows," the reality is that very few do. To my dismay, I have even met French people who don't know him.

Archeologic pastime: My desk with my framed Henri Cartier-Bresson print, my Danish made Dali KATCH bluetooth hifi-speaker, and camera and writing parts. Leica M10 with Leica 50mm Noctilux-M ASPH f/0.95 FLE. © 2017 Thorsten Overgaard.

Archeologic pastime: My desk with my framed Henri Cartier-Bresson print, my Danish made Dali KATCH bluetooth hifi-speaker, and camera and writing parts. Leica M10 with Leica 50mm Noctilux-M ASPH f/0.95 FLE. © 2017 Thorsten Overgaard.

On a corner, next to some parked cars

I feel the city of Paris and/or Leica Camera AG should put up a display of some sort behind Gare Saint-Lazare with the story of the photograph, because nobody knows. During my first days in Paris, I was so busy getting to places that I walked right by the Saint-Lazare station without noticing it, and (ironically) the fact that several mornings I had been standing there, waiting for a green light, in the exact spot where Henri Cartier-Bresson stood 85 years ago.

No, that’s not Henri, but he’s standing in the exact line of view that Henri Cartier-Bresson stood 85 years ago. Or more likely, he might have been in the garden behind (Google maps).

Not what strikes you as a specially significant location in the history of photography, but this is actually the exact line of view Henri Cartier-Bresson was at when he took the photo. Only to be determined was if it was here, or a few steps back. Leica TL with 50mm f/2.0.

The fence, the clock tower and the rooftops

After some days in Paris, I got into my archeological pastime project. I visited the scene. The dramatic metal fence is still the same, which is astonishing, but it also confused me because any place along Rue de Londres looked like it could be the spot. It wasn’t until I consulted the image I had saved on my iPhone that I realized I was more than 200 feet off.

I looked at the patterns in the fence first, but that led me astray a few times. While distinct, there are 3-4 places that have those exact details. I looked at where the tower was placed in the photograph, and finally, I refined it to the clock tower, the angle of the rooftops, and (as the most important guide) the still-existing blurred little tower sticking up in the background to the right of the clock tower—most likely one of the chimneys of the Hilton Paris Opera building.

That’s how I nailed the location to be exactly the angle from where you wait for the green light in the Place de l’Europe roundabout where Rue de Londres meets Rue de Liège. That’s the exact angle it was taken from.

I also know it must have been taken early morning on a fairly overcast day.

Henri Cartier-Bresson "never" cropped any photo

Another rule Henri Cartier-Bresson was famous for was that he "never cropped a photo," and even today, if you license one of his photographs for magazine or postcard printing, you are not allowed to crop them at all.

The irony is that "Behind St. Lazare" was cropped because the fence was in the way. To figure out what lens he used, we must take the 20%-25% crop of the left side of the photograph into consideration as well.

That’s what places him up in the garden on the corner, or whatever was there in 1932.

There is also a misalignment in the height of the black metal fence when photographing from ground level today, compared to the original photograph. It seems that Henri Cartier-Bresson was standing on higher ground back then than what is available today.

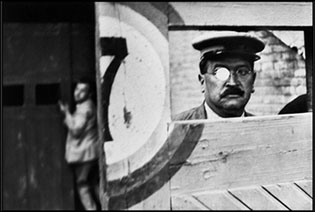

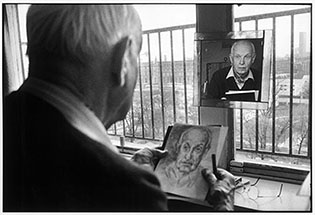

The original negative from “Behind St. Lazare.” I tested with a 35mm and a 50mm lens, and my conclusion is that he must have used a 50mm because of the blur of the tower in the background. Any 35mm lens would result in a sharper background than is the case. Photo by John Leongard.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Buy the Best-Selling eBook by Thorsten Overgaard:

"Finding the Magic of Light"

"I have just been reading your eBook last night, which opened my eyes for more than

I have been thinking about before. You have a great sensitivity that I feel

connected with, and I enjoyed every word."

"I am reading your book, Finding the Magic of Light. Exactly what I crave."

"I find your books very helpful and thought-provoking."

"A must have. Personally useful for street photography."

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Also available in German:

"Die Magie des Lichts Finden"

DE DE |

|

In this easy to read and apply eBook, Thorsten Overgaard takes you on a journey to see, understand and simply use light.

"One of the most important ways to get an aesthetic and pleasant picture is to find the good light."

"Finding the Magic of Light"

New 2nd edition (April 2015)

eBook for computer and iPad.

(87 pages)

Only $47

Order now - Instant delivery.

(Note: If you bought the first edition of this book, this new edition is free. Simply send an e-mail for your free update).

★

★

★

★

★

★

|

| |

|

|

|

Henri Cartier-Bresson: In his own words

“There was a plank fence around some repairs behind the Gare Saint-Lazare train station,” Henri Cartier-Bresson said. “I happened to be peeking through the gap in the fence with my camera at the moment the man jumped. The space between the planks was not entirely wide enough for my lens, which is the reason why the picture is cut off on the left”.

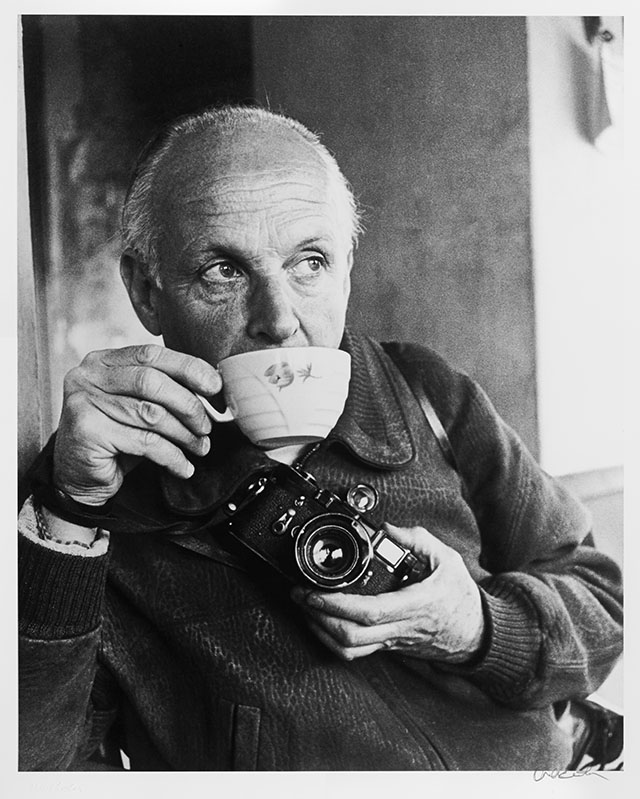

Henri Cartier-Bresson with his Leica M3 in 1964. Photo by Ara-Güler.

Understanding Henri Cartier-Bresson in 6 seconds

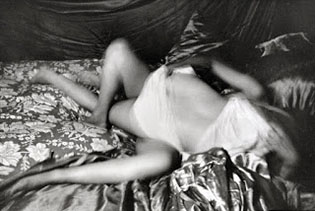

I notice that Henri Cartier-Bresson had a period from 1931-1934 where his images were clearly inspired by Cubism, and he did some really inspiring and impressive work. He seemed very enthusiastic.

Then he had a period with quite a lot of Mexican women who were mostly nude (which I guess was also an enthusiastic period, though those photographs are not generally known), followed by a serious political period. After that, he experienced commercial success doing portraits and reportages for magazines, but he seemed less enthusiastic about it himself. Eventually, he went back to painting.

|

|

|

| 1932 - Cubism |

|

1933 - Cubism |

|

|

|

| 1934 - Spanish and Mexican women |

|

1946 - Reportage |

|

|

|

| 1961 - Portraits |

|

1996 - Painting |

Understanding Henri Cartier-Bresson in six seconds: From being enthusiastic and able to implement advanced Cubism into wordless images, then a few years with Mexican women, to the established years as a gifted portrait photographer, and finally back to his original purpose as a painter.

Which Leica lens did Henri Cartier-Bresson use?

“Henri Cartier-Bresson always used a 50mm,” the saying goes. But it’s also known that he did, in fact, use other lenses. It’s more fair to presume that his preferred lens was the 50mm, just like most Leica photographers use one lens more than 95% of the time. Yes, Henri Cartier-Bresson likely did the same. In an interview years later, Henri Cartier-Bresson shared some details about his choice of lenses:

“The 50mm corresponds to a certain vision and at the same time has enough depth of focus, a thing you don’t have with longer lenses. I worked with a 90mm. It cuts much of the foreground if you take a landscape, but if people are running at you, there is no depth of focus. The 35mm is splendid when needed, but extremely difficult to use if you want precision in composition. There are too many elements, and something is always in the wrong place. It is a beautiful lens at times when needed by what you see. But very often it is used by people who want to shout. Because you have distortion, you have somebody in the foreground, and it gives an effect. But I don’t like effects.”

In 1932, when he made the photograph, a 35mm lens existed, but only the f/3.5 Elmar, which would not produce the narrow depth of field that the clock tower in the background shows. I did some 35mm photos at f/3.5, and the background is much sharper, even taking into consideration that the original photo from 1932 has mist and/or steam from the trains. The first 35mm Summilux f/1.4 wasn’t made until 1961, so he certainly didn’t use that one.

Maybe as simple as this: He used his first Leica, the Leica-Couplex (Leica D) with the 50mm Elmar f/3.5. He was said to black out the silver parts of the camera.

| |

|

| |

Maybe as simple as this: He used his first Leica, the Leica-Couplex (Leica D) with the 50mm Elmar f/3.5. He was said to black out the silver parts of the camera. |

| |

|

So, most likely, he used a 50mm Elmar f/3.5, which was on his first camera he got just two years before. I would suggest the possibility that he might have had a 50mm Hektor f/2.5 (made from 1930) because of the depth of field, as the depth of field almost suggests he might have used a 73mm Hektor f/1.9 (made from 1931), but then he would have had to have been even further back. The 73mm is my idea, simply because it existed at that time, not that Henri Cartier-Bresson was ever known for using that lens. According to himself, he did use 90mm lenses as well, but a 90mm Elmar f/4.0, which was the one available in 1932, would put him very far back (giving a much blurrier fence shadow in the foreground) and, at f/4.0, would not cause the clock tower to be as out of focus as it is.

In my calculations, his point of view was in the crossing marked on the map. But the 20%-25% crop of the photo almost places him up in the garden on the corner. And then the more blurred background than a 50mm Summicron-M f/2.0 produces today must be explained as the result of motion blur and steam from the trains. The photograph was likely taken at 1/60th or 1/30th of a second, judging from the blurry silhouette of the jumping man. At 1/125th of a second, he would be almost without motion blur.

Henri Cartier-Bresson: My conclusion

Had I known my archaeological pastime project in Paris would be this demanding, I might have prepared better. I still feel I should go back next time, climb the fence to the garden behind, and bring a small ladder to find the exact point where he was.

What we can learn from “Behind Gare Saint-Lazare”

Henri Cartier-Bresson was only 23 years old when he captured “Behind Gare Saint-Lazare.” In my opinion, this should fuel some afterthoughts on age and experience versus just getting out and photographing. If one examines the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson, one will see that he did some amazing work in 1931-1932 as a young man, fired up by his search for “geometric pleasure” inspired by painting, before he headed into other subjects.

Henri Cartier-Bresson on MOMA (Museum of Modern Art, New York).

Henri Cartier-Bresson

The definition of "Street Photography"

To me, the now all-fashionable term “Street Photography” is simply taking a camera to the street and capturing what you see.

The results may be as different and personal as your viewpoint. Some will see the beauty of light, others the less fortunate in the streets (also known as the “human condition” category), others will see funny gestures, and some will focus on characteristic people they see on 5th Avenue. It’s all happening in the streets, for you to capture with your camera, and if you happen to live in Qatar, the street may extend to the desert where (surprisingly many) people walk, ride, or drive, just as the “streets” of Greenland may differ quite a bit from the streets of London.**

Art historians' take on Behind Staint-Lazare

I’ve read analyses of the photograph as a different take on St. Lazare because most of the photographers and artists of that time were more taken by the architecture inside the station. I don’t think Henri Cartier-Bresson for a second thought about this or tried to make any alternative take on the station. In fact, he probably couldn’t care less if the station was there in the background or not. The explanation is rather that the photograph simply happened.

Gare Saint-Lazare by Claude Monet.

Henri Cartier-Bresson: Geometric pleasure

But the photograph has some of the well-known elements that often make up a Henri Cartier-Bresson photograph: There is the element of timing (“the decisive moment”), which in this case seems more important than anything else, and then there are the pleasing geometric shapes that align with each other and create a strong image. “The greatest joy for me is geometry; that means a structure,” as Henri Cartier-Bresson said.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

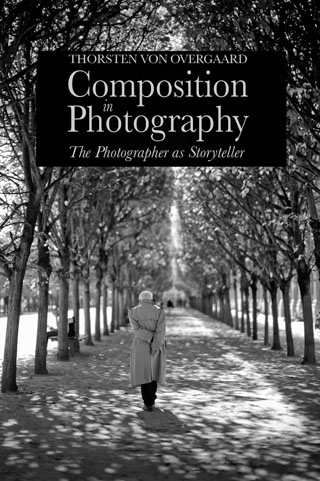

Buy the new eBook

"Composition in Photography"

by Thorsten von Overgaard |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Composition in Photography

- The Photographer as Storyteller

This book will inspire your photographic eye and make you wonder about all the possibilities you can now see.

In this exciting new book Thorsten Overgaard expands and simplifies the subject of composition. It's elevated from geometric patterns to actual storytelling by practical use of space, rhythm, time, colors, emotions and intuition in your photography.

- The Basics of Composition.

-

Composition in the Third Dimension.

- Picture Stories.

- Accenturating with Light.

- Photograph as a Melody.

- Which lens are you?

- Fear of sharpness?.

- Vanishing Point.

- The most important

element of composition

- What is the unknown secret

why it is you mostly can't get

the Rule of Thirds to work?

- How does a camera see

differently than the eye?

- What does quantum physics and

photography have in common?

- What's the greatest adventure you can

set out on in photography these days?

- A Sense of Geometry.

Only $398.00.

Order now. Instant delivery.

864 pages. 550 Illustrations. |

|

"It’s your best work so far"

"I’m being gently led"

" I love this book!!!"

"The book is incredible"'

"It’s like therapy for the human spirit."

"Beautiful and inspiring"

"Full of practical advice

and shared experience"

'I love how hands-on and

laid back Thorsten's witting style is"

"Inspiring"

"Intense and thought-provoking" |

|

| |

|

|

|

100% satisfaction of money back. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Never delete anything

Also, I can’t help imagining if Henri Cartier-Bresson had been using a digital camera. Would he have deleted the photo when he realized that the whole left side was missing because of the fence? I doubt he would have. It speaks to his strong sense of picking a good photograph even before it happens, which was the case with this photograph. He knew that it would work, even though he had to crop away a great deal of it.

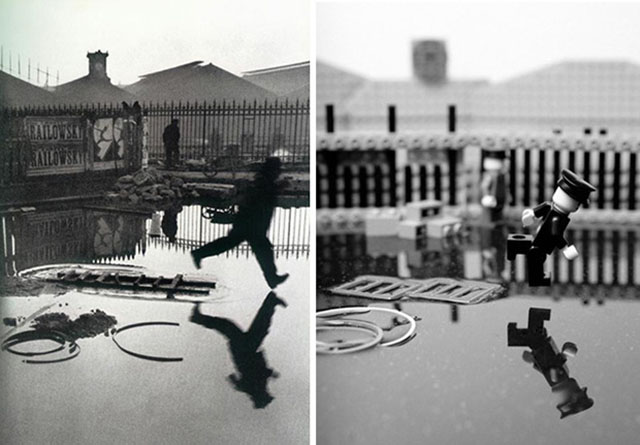

Remaking "Behind Gare Saint-Lazare"

Of course, I had a secret hope that something would happen in front of my camera that would make a great photo, one that would draw lines back to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph but also be an entirely new image. Nothing ever happened like that. Instead, I had parked cars in the view and a few people walking while looking at their iPhones. I did think of the possibilities of clearing the street of cars, drenching it with water, and having a ballerina jump into the frame. Perhaps the best recreation I’ve seen so far is the LEGO recreation of the famous photograph, and maybe it’s supposed to be like that: The "Behind Gare Saint-Lazare" has already been done by Henri Cartier-Bresson. There is nothing more to add.

Henri Cartier-Bresson 1932 and the LEGO remake by Mark Stimpson in 2013.

I hope you enjoyed today’s Story Behind that Picture. As always, feel free to e-mail me with ideas, suggestions and questions.

![]()